WayToCoppersmith0x01

Solving Small root for Modular Bivariate Polynomial

Coron’s Technique

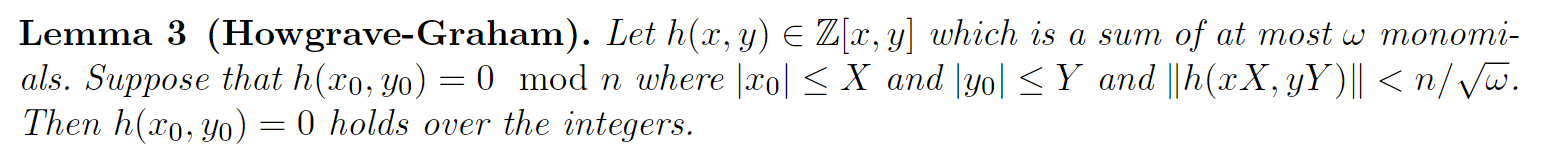

Howgave-Graham’s condition

For proof, just recall the inequality we metioned last blog. There is a grace way to proof this.

PROOF:

According to lemma 3, we have:

$$ \begin{aligned}\vert h(x_0,y_0)\vert &= \vert \sum h_{i,j} x_0^i y_0^j \vert = \vert \sum h_{i,j} X^jY^j(x_0/X)^i(y_0/Y)^j \vert \\\\ &\le \sum \vert h_{i,j}X^jY^j(x_0/X)^i(y_0/Y)^j \vert \\\\ &\le \sum \vert h_{i,j} X^iY^j \vert \\\\ &\le \sqrt{\omega}\Vert h(xX,yY) \Vert \lt n \end{aligned} $$then given $h(x_0,y_0) \equiv 0 \mod n$, we have $h(x_0,y_0) = 0$.

The lemma there also descripted as follow:

Bivariate Integer Polynomials Case

After we process the univariate case in last post, now with the similar method , we can also find small root on bivariate polynomial ring under Howgrave’s condition.

In the bivariate integer polynomial case, we can utilize a similar approach to the univariate scenario that was covered previously. The key is to leverage Howgrave’s condition to construct a matrix whose linear space forms a lattice. By applying the LLL algorithm to this lattice, we can then obtain a set of polynomials with smaller coefficients that share the same roots.

Nevertheless, the bivariate case presents an additional challenge - we need to find two distinct polynomials in order to solve for both variables, $x$ and $y$. The general strategy is as follows:

- Construct a matrix whose rows correspond to the desired polynomial constraints, taking into account Howgrave’s condition.

- Apply the LLL algorithm to this matrix to obtain a reduced basis, which will include two or more polynomials with smaller coefficients.

- Analyze the resulting polynomials to identify a pair that can be used to solve for the values of x and y.

This approach allows us to find the small roots of bivariate integer polynomials, under Howgrave’s condition.

The most significant problem is the structure of our matrix.

For example

Coron’s Construction

With familiar idea, we gonna set a lattice with a suitable determinant for lattice reduction , this process also reduce our coefficients.

Build shift polynomials for our matrix.

Set our target with the form below:

$$ p(x,y) = \sum_{0 \le i, j \le \delta} p_{i,j} x^i y^j $$Obviously, we note the coefficients as $p_{i,j}$. Remember that our goal is to reduce the coefficients to smaller ones in two independent polynomials letting us to find roots directly with resultant or Gröbner basis. With condition given in Howgrave-Graham, we start to build some polynomials.

That is:

We are looking for an integer root $(x_0,y_0)$ such that $p(x_0,y_0) = 0$ and with the bound $\vert x_0 \vert \le X, \vert y_0 \vert \le Y$.

Assumption 1: $p(x,y)$ is irreducible.

Of course, if not , just use the factor as new $p(x,y)$.

Fact: shift ploynomials share the same root with our target $F(x,y)$

It’s trivial to attention the fact.

In Cor[07] we build.

$$ S_{a,b}(x,y) = x^a y^b \cdot p(x,y) ,\text{for}\quad 0 \le a,b \lt k \tag1 $$$$ r_{i,j}(x,y) = x^i y^j \cdot n ,\text{for}\quad 0 \le i,b \lt k+\delta \tag2 $$Matrix $S$

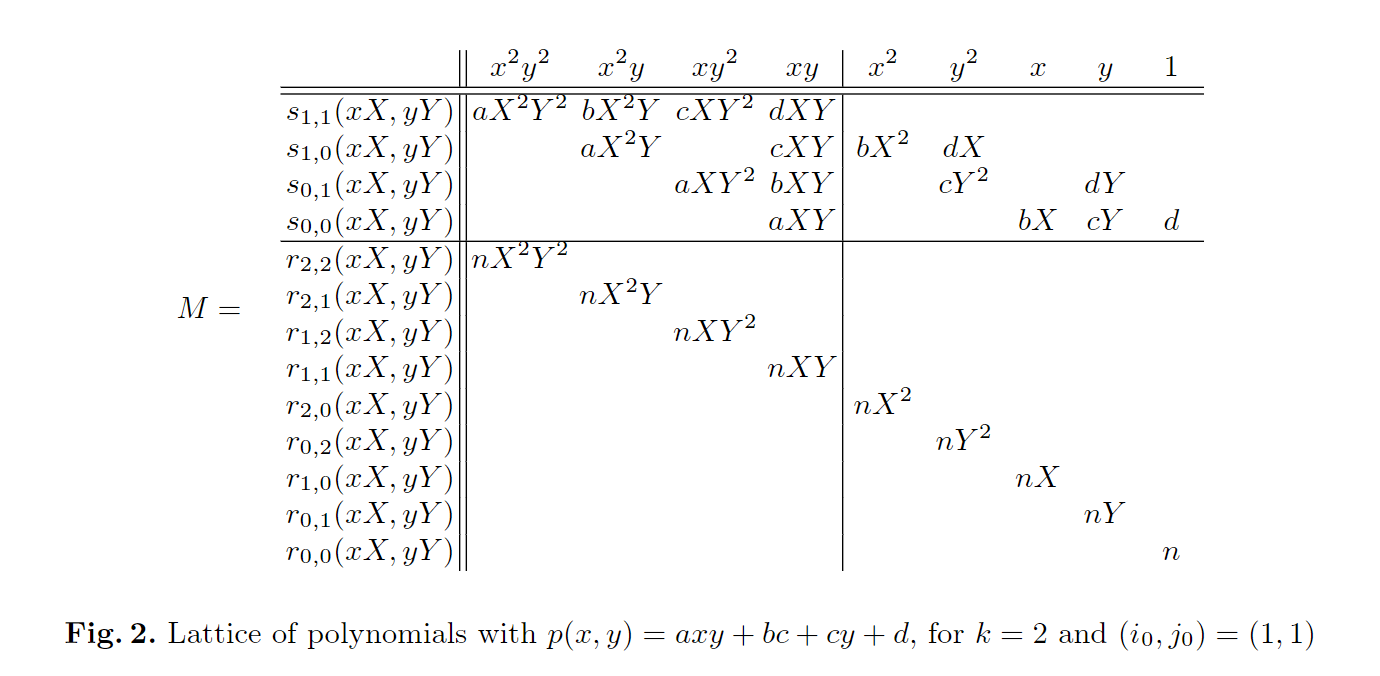

Let $S$ be the matrix of row vectors obtained by taking the coefficients of the polynomials $S_{a,b}(x,y)$ for $0 \le a, b \lt k$, (choose $k \in \mathbb{N}$ sufficiently large) and consider the $k^2$ polynomials for which we only consider the monomials $x^{i_0 +i}y^{j_0 +j} \text{for}\quad 0 \le i,j \lt k$, where the index $(i_0,j_0)$ is given. ( $0 \le i_0,j_0 \lt \delta $).

For parameter $n$ in $(1),(2)$:

$$ n \coloneqq \vert \det S \vert $$

Then, let

$$ W = \max_{i,j} \vert p_{i,j} \vert X^j Y^j = \vert p_{uv} \vert X^u Y^v $$

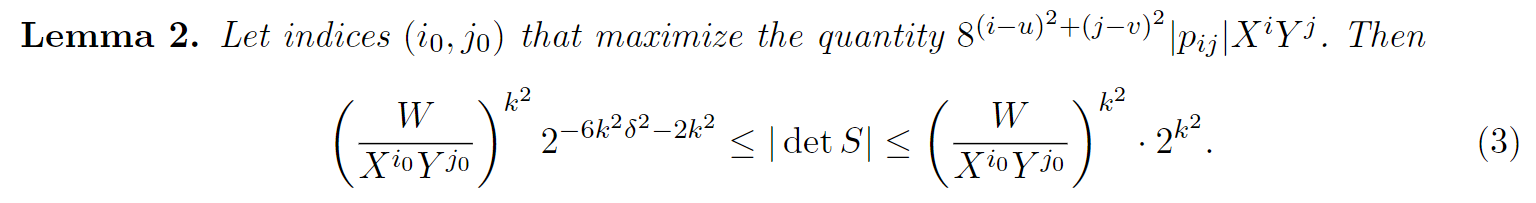

Proof of this inequality is pretty complex , before that we need to know the purpose of introducing Lemma 2:

We are still on the road to find our shift polynomial

Assumption 2:

$$ XY \lt W^{2/(3\delta) -1/k}2^{-9k} $$This gives

$$ \begin{aligned} W &\gt (XY)^{\delta}\cdot2^{9\delta^{2}} \\\\ n &= O(W^{k^2}) \end{aligned} $$so that matrix $S$ is invertible.

Finally, we can descript our shift polynomial $h(x,y)$ .

Let $h(x,y)$ be a linear combination of the polynomials $s_{a,b}(x,y)$ and $r_{i,j}(x,y).$ Since we have that $s_{a,b}(x,y)=0$ mod $n$ for all $a,b$ and $r_{i,j}(x,y)=0 \mod n$ for all $i,j$,we obtain:

$$ h(x_0,y_0)=0 \mod n. $$The following lemma, due to Howgrave-Graham [13], shows that if the coefficients of polynomial $h(x,y)$ are sufficiently small, then $h(x_0,y_0)=0$ holds over the integers. For a polynomial $h(x,y)=\sum_{i,j} h_{ij}x^{i} y^{j}$, we define $\Vert h(x,y) \Vert ^2:=\sum_{i,j}\vert h_{ij}\vert^2.$

Lattice $L$

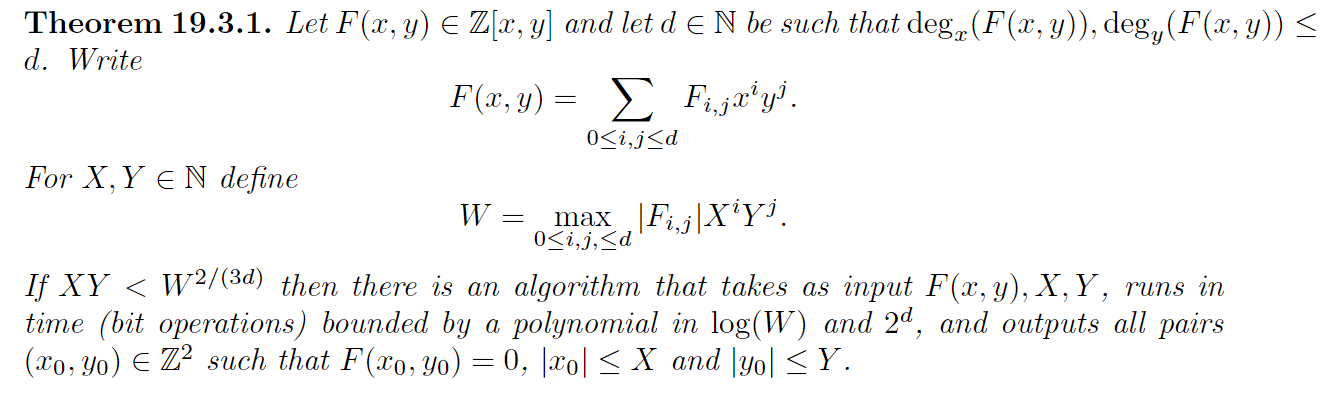

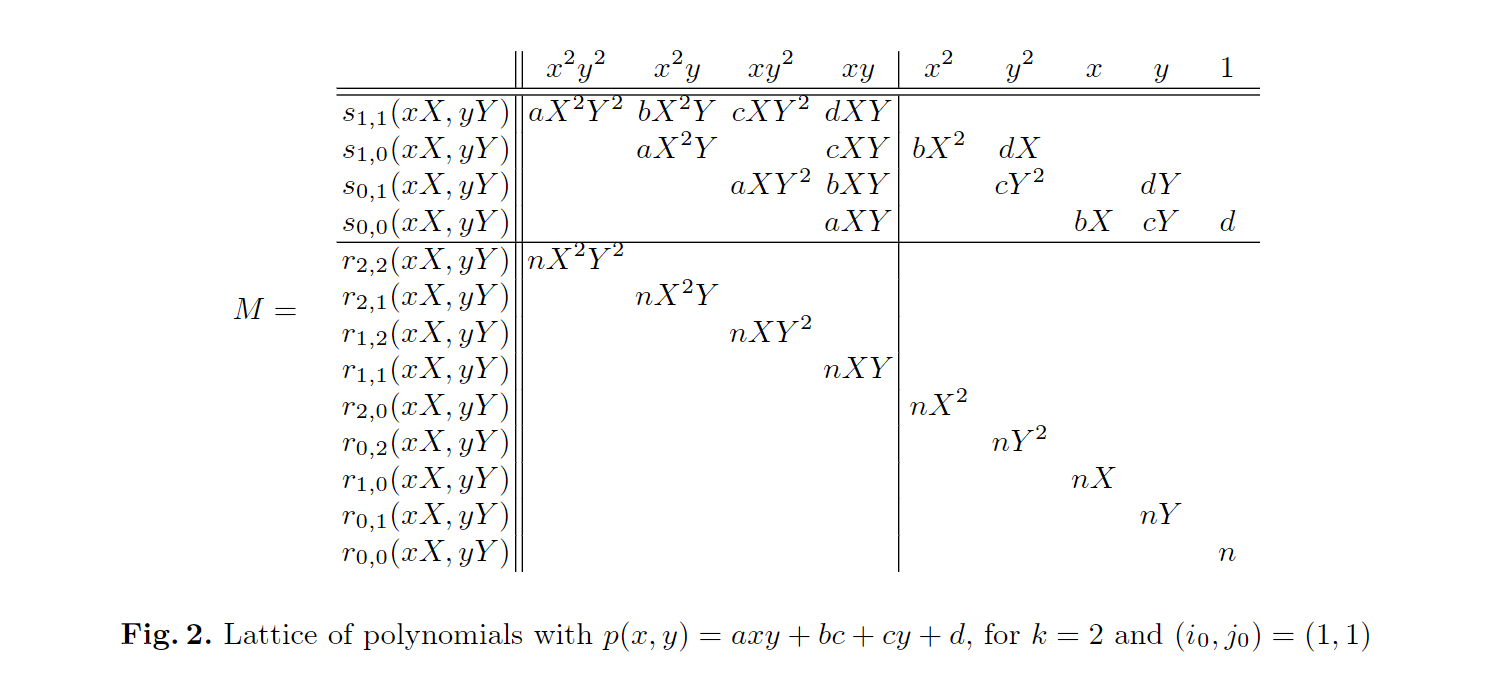

We consider the lattice $L$ generated by the row vectors formed with the coefficients of polynomials $s_{a,b}(xX,yY)$ and $r_{i,j}(xX,yY).$ In total, there are $k^2+(k+\delta)^2$ such polynomials; moreover these polynomials are of maximum degree $\delta+k-1$ in $x,y$, so they contain at most $(\delta + k)^2$ coefficients. Let $M$ be the corresponding matrix of row vectors;

$M$ is therefore a rectangular matrix with $k^2+(k+\delta)^2$ rows and $(k+\delta)^2$ columns (see Figure 2 for an illustration). Observe that the rows of $M$ do not form a basis of $L$ (because there are more rows than columns), but $L$ is a full rank lattice of dimension $(k+\delta)^2$ (because the row vectors corresponding to polynomials $r_{i,j}(xX,yY)$ form a full rank lattice).

With our idea to find $h(x,y)$, we build $M$. Notice that choosing a block in $M$ can done the task easier.

Nonetheless, that’s not enough.

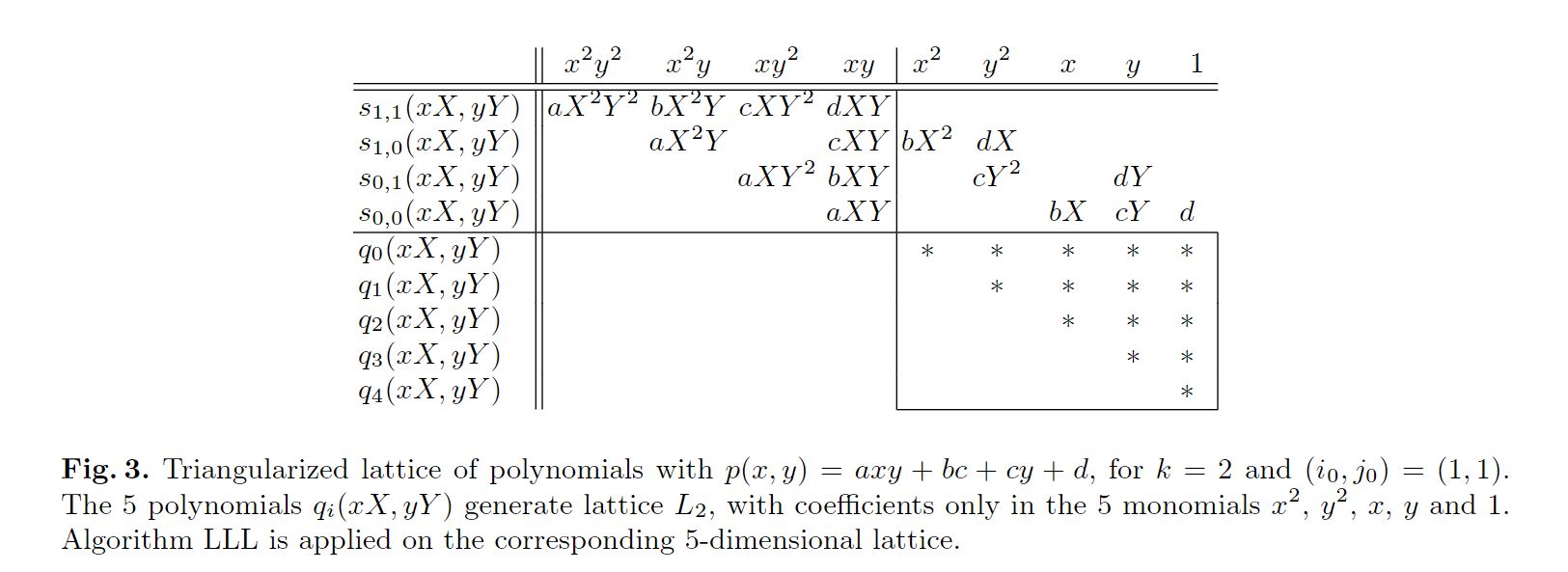

Sublattice $L_2$

Formally, we choose the sub lattice $L_2$ with $\omega$ dimensions

$$ \omega \coloneqq (\delta+K)^2 -k^2 = \delta^2 + 2k\delta $$A matrix basis for $L_2$ can be obtained by fırst triangularizing $M$ using elementary row operations and then taking the corresponding submatrix (see Figure 3).

Now, the exciting moment.

Apply LLL to $L_2$!

Get a non-zero polynomial $h(x,y)$ that satisfies $h(x_0,y_0) = 0 \mod n$ and

$$ \Vert h(xX,yY)\Vert \leq2^{(\omega-1)/4}\cdot\det(L_2)^{1/\omega} $$From H-G bound:

if :

$$ 2^{(\omega-1)/4} \cdot \det L_2 ^{1/\omega} \le \frac{n}{\sqrt\omega} $$then $h(x_0,y_0) = 0$ holds in $\mathbb{Z}$.

Proof of solvability

First,the strategy of selecting submatrices allows us to avoid getting multiples of the original polynomial. Then, $p(x,y)$ is irreducible and $h(x,y)$ are algebraically independent with a common root $(x_0,y_0)$. Therefore, taking:

$$ Q(x) = Resultant_y(h(x,y),p(x,y)) $$gives a non-zero integer polynomial such that $Q(x_0)= 0$. Using any Standard root-finding algorithm, we can recover $x_0$, and finally $y_0$ by solving $p(x_0,y)=0$. This proofs the solvability.

Compute $\det L_2$

Mainly algebra, nothing special.

Calculating determinant with elementary rows transformation need some bridge matrix for block matrix computation.

With our choosing strategy considered, there is a simplified matrix.

Let $M^{\prime}$ be the same matrix as $M$, except that we take the coefficients of polynomials $S_{a,b}(xX,yY)$ and $r_{i,j}(xX,yY)$; matrix $M^{\prime}$ has $k^2+ (\delta + k)^2$ rows and $(k+\delta)^2$ columns. And we remove the $X^i Y^j$ powers.

$$ M^{\prime} = \begin{bmatrix} S & T \\\\ nI_{k^2} & 0 \\\\ 0 & nI_{\omega} \end{bmatrix} $$Detail:

Matrix $S$ is previously defined square matrix of dimension $k^2$, while $T$ is matrix with $k^2$ rows and $\omega = k^2 + 2k\delta$ columns. Let $L^\prime$ be a lattice generated by the rows of $M^{\prime}$, in other word , we set $L^{\prime}$ in the row space of the matrix $M^{\prime}$, and let $L_2^\prime$ be the sublattice where all coefficients corresponding to monomials $x^{i+i_0}y^{j+j_0}$ for $0 \le i, j\lt k$ are set to zero. Note that lattice $L^{\prime}$ corresponds to lattice $L$ without the $X^iY^j$ powers, whereas lattice $L_2^\prime$ corresponds to lattice $L_2$.

Note that:

$$ S^\prime \cdot S = n I_{k^2} $$Namely $S^\prime$ is (up to sign) the transpose of the co-factor matrix of $S$, verifying $S^\prime\cdot S=(\det S)I_{k^2}.$ of $M^{\prime}$; this gives the following matrix:

$$ M_2'=\begin{bmatrix}I_{k^2}&0&0\\\\-S'&I_{k^2}&0\\\\0&0&I_\omega\end{bmatrix}\cdot M'=\begin{bmatrix}S&T\\\\0&T'\\\\0&nI_\omega\end{bmatrix} $$where $T^\prime=-S^{\prime}\cdot T$ is a matrix with $k^2$ rows and $\omega$ columns. By elementary operations on the rows of $M_2^{\prime}$, we obtain:

$$ M_3^{\prime}=U\cdot M_2^{\prime}=\begin{bmatrix}S&T\\\\0&T^{\prime \prime}\\\\0 & 0\end{bmatrix} $$where $T^{\prime\prime}$ is a square matrix of dimension $\omega$. We obtain that $T^{\prime\prime}$ is a row matrix basis of lattice

$$ \begin{aligned} \det L^{\prime}&=\vert \det\begin{bmatrix}S&T\\\\0&T''\end{bmatrix}\vert \\\\&=\vert \det S\vert \cdot\vert \det T^{\prime\prime}\vert \\\\ &=\vert \det S\vert \cdot\det L_2^{\prime}\\\\ &=n\cdot\det L_2^{\prime}\end{aligned} \tag4 $$So our target changes to compute the determinant of $L^{\prime}$. The polynomial $p(x,y)$ being irreducible, the gcd of its coefficients is equal to $1$.

The gcd of the coefficients of $p(x,y)$ being 1 implies that the entries of $M^{\prime}$ are coprime, which allows for the columns of $M^{\prime}$ to be transformed through elementary operations into an identity matrix block. This is possible because there are no common factors that restrict the linear combinations needed to zero out entries and simplify the matrix. The unimodular transformation preserves the determinant, ensuring that the fundamental properties of the lattice defined by $M^{\prime}$ are maintained.

$$ M_4^\prime=M^\prime\cdot V=\begin{bmatrix}I_{k^2}| 0\\\\nV\end{bmatrix} $$By elementary row operations on $M_4^{\prime}$ based on $V^-1$ we obtain :

$$ M_5^{\prime}=\begin{bmatrix}I_{k^2}&0\\\\0&V^{-1}\end{bmatrix}\cdot M_4'=\begin{bmatrix}I_{k^2}&0\\\\&nI_{(\delta+k)^2}\end{bmatrix}=\begin{bmatrix}I_{k^2}&0\\\\ nI_{k^2}&0\\\\0&nI_\omega\end{bmatrix} $$$$ M_6^{\prime}= U^\prime \cdot M_5^{\prime}=\begin{bmatrix}I_{k^2}&0 \\\\ 0 & n I_\omega \\\\ 0&0\end{bmatrix} $$$$ \det L'=\det\begin{bmatrix}I_{k^2}&0 \\\\ 0&nI_\omega\end{bmatrix}=n^\omega \tag5 $$Combining equations $(4)$ and $(5)$, we obtain:

$$ \det L_2'=n^{\omega-1} $$Finally we can recover $\det L_2$ from $\det L_2^\prime$:

$$ \begin{align} \det L_2&=\det L_2^{\prime}\cdot\frac{\prod\limits_{0\leq i,j<\delta+k}X^iY^j}{\prod\limits_{0\leq i,jThis obtained:

$$ 2^{\omega\cdot(\omega-1)/4}\cdot\frac{(XY)^{(\delta+k-1)\cdot(\delta+k)^2/2-(k-1)\cdot k^2/2}}{(X^{i_0}Y^{j_0})^{k^2}}\leq\frac n{\omega^{\omega/2}}. $$Consider $n \coloneqq \vert \det S \vert$ and its bound, with $\sqrt\omega \le 2^{\omega/2}$:

$$ 2^{\omega\cdot(\omega-1)/4}\cdot(XY)^{(\delta+k-1)\cdot(\delta+k)^2/2-(k-1)\cdot k^2/2}\leq W^{k^2}\cdot2^{-6k^2\delta^2-2k^2}\cdot2^{-\omega^2/2} $$This condition is satisfied if

$$ XY \lt W^{\alpha}\cdot 2^{-9\alpha} $$where:

$$ \alpha = \frac{2k^2}{\delta\cdot (3k^2+k(3\delta-2)+\delta^2 -\delta)} $$And Finally we shall get our target bound (a sufficient one):

$$ XY \lt W^{2/(3\delta)-1/k}\cdot2^{-9\delta} $$For a weaker one, just take:

$$ XY \lt W^{2/(3\delta)} $$Running time Analysis

The running time is dominated by the time it takes to run LLL on a lattice of dimension $\delta^2+2k\delta$, with entries bounded by $\mathcal{O}(W^{k^2})$.Namely, the entries of a matrix basis for $L_2$ can be reduced modulo $n\cdot X^iY^j$ on the columns corresponding to monomial $x^i y^j$, because of polynomial $r_{i,j}(xX,yY)=n\cdot X^i Y^j x^i y^j$.

Substituting the running time analysis results of the two algorithms, the running time is bounded by:

$$ \mathcal{O}(\delta^6 k^12 \log^3{W}) $$using LLL, and $\mathcal{O}(\delta^5 k^9 \log^2{W})$.

Under the weaker condition, one can set $k=\lfloor\log W\rfloor$ and do exhaustive search on the high order $\mathcal{O}(\delta)$ unknown bits of $x_0$. The running time is then polynomial in $2^\delta$ and $\log W$. For a fixed $\delta$, the running time is $\mathcal{O}\log^{15} W$ using LLL.

Summary

As usual we consider shifts of the polynomial $F(x, y)$. Choose $k\in\mathbb{N}$ (sufficiently large) and consider the $k^{2}$ polynomials.

$$ s_{a,b}(x,y)=x^a y^b F(x,y)\quad\mathrm{for}\quad 0\leq a,bOne can now consider the $(d+k)^2$ polynomials $Mx^iy^j$ for $0\leq i,j<d+k.$ Writing each polynomial as a row vector of coefficients, we now have a $k^2+(d+k)^2$ by $(d+k)^2$ matrix. One can order the rows such that the matrix is of the form

$$ \begin{pmatrix}S & \* \\\\ MI_{k^2}&0 \\\\ 0&MI_w\end{pmatrix} $$where $w=(d+k)^2-k^2,*$ represents a $k^2\times w$ matrix, and $I_w$ denotes the $w\times w$ identity matrix.

Now, since $M=\det(S)$ there exists an integer matrix $S^\prime$ such that $S^\prime S=MI_{k^2}.$ Perform the row operations

$$ \begin{pmatrix}I_{k^2}&0&0 \\\\-S'&I_{k^2}&0 \\\\ 0&0&I_w\end{pmatrix}\begin{pmatrix}S&* \\\\ M I_{k^2}&0 \\\\ 0&MI_w\end{pmatrix}=\begin{pmatrix}S&* \\\\ 0&T \\\\ 0&MI_w\end{pmatrix} $$for some $k^2\times w$ matrix $T.$ Further row operations yield a matrix of the form

$$ \begin{pmatrix}S&* \\\\ 0&T' \\\\0&0\end{pmatrix} $$for some $w\times w$ integer matrix $T^\prime.$ Coron considers a lattice $L$ corresponding to $T^\prime$ (where the entries in a column corresponding to monomial $x^iy^j$ are multiplied by $X^iY^j$ as in equation (19.2)) and computes the determinant of this lattice. Lattice basis reduction yields a short vector that corresponds to a polynomial $G(x,y)$ with small coefficients such that every root of $F(x,y)$ is a root of $G(x,y)$ modulo $M.$ If $(x_0,y_0)$ is a sufficiently small solution to $F(x,y)$ then, one infers that $G(x_0,y_0)=0$ over $\mathbb{Z}.$

$G(x,y)$ has no common factor with $F(x,y)$.

PROOF:

Assume that $F(x,y)$ is irreducible, then $G(x,y) = \sum_{0 \le i, j\lt k}A_{i,j}x^i y^j$ and so the vector of coeffiencients of $G(x,y)$ is a linear combination of the coefficient vectors of the $k^2$ polynomials $s_a,b(x,y)$ for $0\leq a,b<k.$ But this vector is also a linear combination of the rows of the matrix $\begin{pmatrix} 0 &T^{\prime}\end{pmatrix}$ in the original lattice. Considering the first $k^2$ columns (namely the c olumns of $S)$, one has a linear dependence of the rows in $S.$ Since $\det(S)\neq0$ this is a contradiction.

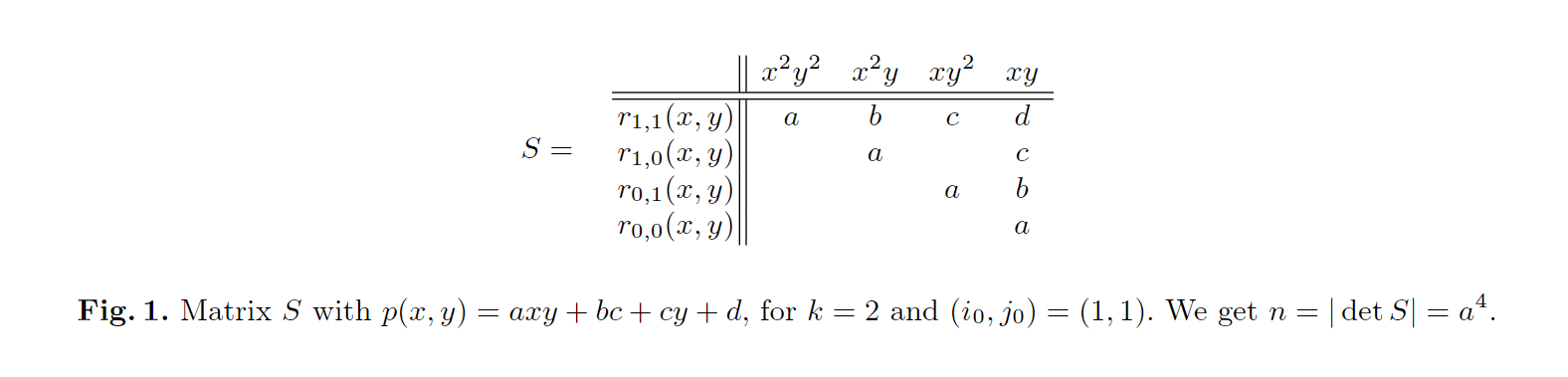

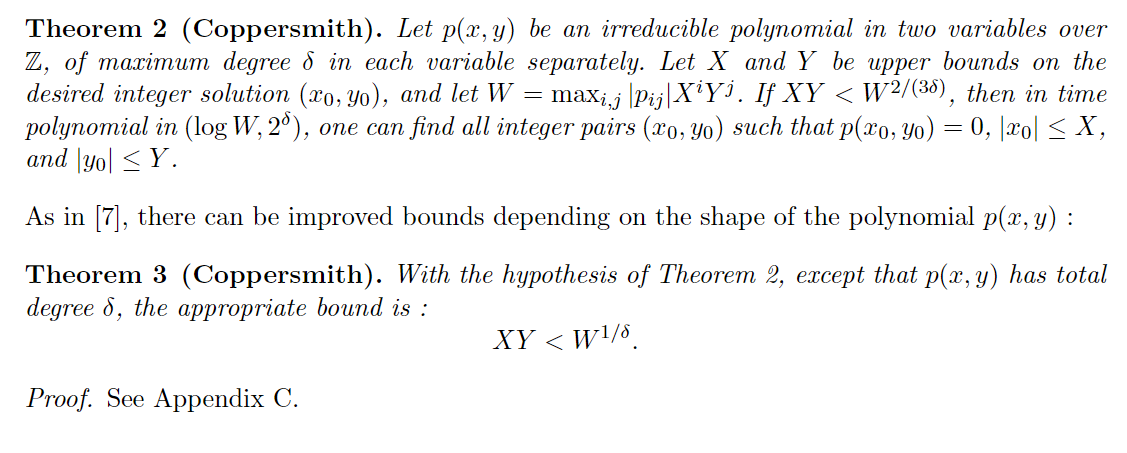

With the main idea above, we can set the two theorem:

Appendix

See in references for an example.

The proof of lemma 2 can be found in the appendix of Cor[07].